A recent thread on GamerGate hub KotakuInAction outlines a plan to “game” Twitter to get viral traction for a tag about the ggautoblocker, the tool created by Randi Harper that allows for wholesale blocking of GG participants, and TheBlockBot, a similar, though more universal tool. The call asks supporters to treat a Twitter campaign as “a large scale attack in an MMO” by coordinating tweets and retweets about the blockers this Thursday at 9pm EST using the hashtag AreYouBlocked?, with the purported aim of “inform[ing] thousands of neutrals on Twitter” and “shaking the earth.”

But the recommended tactics go beyond simple tweets, which is why we’re reporting on this in the first place — some of the discussion around the proposed campaign skews away from the basic idea of “information” and into another realm altogether.

Breaking down the rhetorical foundation

There are a few ideas at the heart of this campaign that should be established first:

- The individuals behind the campaign claim there are “tens of thousands” of people who are on the blocklist who don’t even know it

- The ggautoblocker does in fact weigh in with a list of just over 10,000 at the time of this writing; however, a large number of those accounts show fewer than 40 tweets, few to no followers, and little activity — indicating they may have been throwaway accounts, the creation of which is a common practice for Twitter trolls who are frequently suspended, blocked, or banned.

- That being on a blocklist has any major effect on someone, or is censorship

- This is an oft-discussed idea, and one we’ve explored before, but here’s another take from someone who’s on TheBlockBot list, Martin Robbins, who covers good and bad aspects of blockers as tools.

- That some of the participants being called on aren’t even Twitter users

- The instructions on the subreddit for mobilizing on the night in question include instructions for setting up Twitter accounts, as some of the participants posting on KiA and the thread on the Escapist forum reported no current Twitter accounts, which begs the question of why they would be concerned about blocking on social media in the first place.

- That blocklisting is libellous, at least with TheBlockBot, because blockees are tagged with created labels indicating the reasons they were added; just last month, the bot because a big issue once again, and the question of libel, particularly in the UK, was raised.

- It’s important to note that the tool was profiled on mainstream news sources in 2013 in the UK and has been operation since, but came back under fire last month when a law student in the UK began exploring legal options under data protection laws. The idea of libel was also raised, but the examples used in the post are questionable; Richard Dawkins, for instance, is reportedly labeled “transphobic” by the blocker, but there’s no useful metric to prove or disprove such a claim, or why the person who filed it with the BlockBot team holds that opinion. However, I’m not as familiar with UK laws regarding libel and data protection, beyond the notion that they are reportedly stronger than those in the U.S., and I’m no legal expert, so I cannot speak as to the validity of these claims.

- However, it might be noted that some GG supporters do frequently malign opponents, such as the recent accusations that Randi Harper faked a SWATting (officer response was later confirmed by the Oakland PD). Allegations are frequently made concerning Harper and drugs, as well, and critic Anita Sarkeesian is often labeled a scammer by the same people.

- It’s important to note that the tool was profiled on mainstream news sources in 2013 in the UK and has been operation since, but came back under fire last month when a law student in the UK began exploring legal options under data protection laws. The idea of libel was also raised, but the examples used in the post are questionable; Richard Dawkins, for instance, is reportedly labeled “transphobic” by the blocker, but there’s no useful metric to prove or disprove such a claim, or why the person who filed it with the BlockBot team holds that opinion. However, I’m not as familiar with UK laws regarding libel and data protection, beyond the notion that they are reportedly stronger than those in the U.S., and I’m no legal expert, so I cannot speak as to the validity of these claims.

Problematic issues within the campaign

The phrase “vidya akbar” shows up in the reddit thread, a bastardization of “Allahu Akbar,” a phrase rooted in praise of the greatness of God but often associated with a call to action of Islamic suicide bombers. This misappropriated phrasing is used here by some in relation to issues in gamer culture as a battle cry. While some might move to defend actions like this video mashup of violent scenes from the Law and Order: SVU episode “Intimidation Game” with tracks of the cry on repeat, that troubling mix of phrasing with rape and torture imagery disturbs on many levels. In the comments, however, it’s treated as a joke, called awesome; the effort is praised. Some commenters just want to know if the woman is raped or not. No one seems concerned about any deeper issues.

This treatment and subsequent reaction, while more serious on the face than a Twitter campaign to make a hashtag trend, speaks to larger issues with GamerGate as a movement, a label many within the faction decry even whilst mounting such campaigns. As part of this campaign, they are recruiting new and past Twitter users, distributing “attack” instructions, and preparing battle strategies, all ostensibly to demonstrate their power in the industry and on social media. But this treatment of everything from the Twitter campaign to misappropriation of religious phrasing to libel and SWATting as a “game” is what is leading some to label GamerGate themselves as a terrorist group, and I can’t imagine moves like this will do much to disabuse anyone of that notion.

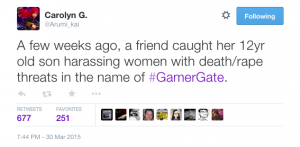

Late last month, a Twitter user named Carolyn G. (@Arumi_kai) reported that “A few weeks ago, a friend caught her 12yr old son harassing women with death/rape threats in the name of GamerGate.” She said she shared the story because that child, and others, were learning to see these tactics as just a game. Nothing real. With rhetoric like that used for this campaign, one might guess it isn’t only impressionable pre-teens who feel that way, as many of the non-anonymous faces of GamerGate are adults.

Late last month, a Twitter user named Carolyn G. (@Arumi_kai) reported that “A few weeks ago, a friend caught her 12yr old son harassing women with death/rape threats in the name of GamerGate.” She said she shared the story because that child, and others, were learning to see these tactics as just a game. Nothing real. With rhetoric like that used for this campaign, one might guess it isn’t only impressionable pre-teens who feel that way, as many of the non-anonymous faces of GamerGate are adults.

Implications and the future

GamerGaters often speak, in recent months, of how long the movement has been going. Six months since the initial cries of “ethics in games journalism!” Seven. Look at what we’ve accomplished, they say. Look at our power. But what is that power? Is it the power to change gaming media, or is it the silencing power of intimidation tactics? The power to recruit others under a banner to accomplish… what?

It is the kind of rhetoric demonstrated above, rhetoric rooted in intolerance and terrorism, that completely shuts down the possibility of communication. It removes the chance at (re)building a sense of community or any kind of cohesive gamer identity that is based in and on diversity. And sadly, that is not the aim of some of the men and women who align themselves with the GamerGate movement.

In the moment of feeling threatened GGers have turned instead to threats, oft times with the rhetoric of extremism (thus the cries of “Vidya Akbar” and the terrorism/SVU hostage mashup video). Perhaps this shows us not only a weakness in the GG movement, but a weakness in American/global society as well when it comes to communicating one’s feelings in moments of (di)stress. Does this indicate that there is a need for a rhetoric of dissent? Do we need to educate people on not only the means of persuasion, but the means of persuasion in a situation where one’s own identity (or the perception of said identity) is at risk? Because isn’t that what it really all comes down to? The belief of a vocal minority (maybe) of GGers that their identity as gamers is being challenged and co-opted by a group of women who are “new” to gaming and out to destroy them and their manly endeavors?

This belief further demonstrates not only why we need more diversity in games and the games industry, but demonstrates what some of the long term ramifications of a lack of diversity can be. The perception that women didn’t play, develop, or care about games until recently has fueled this violent and territorial response. The reality is that there are women who game who grew up with gaming mothers and are now raising gaming daughters of their own, but until recently they had not found a place in the centralized community for themselves. They were previously relegated to the margins where they could not be ostracized or criticized by other gamers and/or those around them who also perceived gaming an unseemly undertaking for a woman.

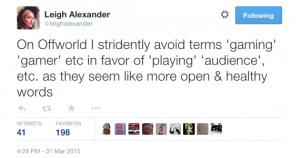

On Twitter, Leigh Alexander said recently that, on the relaunched Offworld, she’s avoiding the word “gamer” in favor of terms like audience and players. She says she feels these are healthier, and who can say if that’s true, but maybe there is something to the idea of a new label bridging a gap that, since September, has only seemed to widen. If we are all players, playing in our own ways, engaging on our own terms, perhaps we can find our way back to some common ground. There may not be a community to be had, one uniform whole under a moniker like “gamers,” but if we work to rearrange while understanding there is no homogeneity and we don’t want homogeneity — that it is time to move past the grizzled white cis-male hetero hero of every game, in every setting; that it is time to stop equating video games with trenchcoat-clad nerds; that is is time to expand our understanding of the interplay between what we play and who we are — then perhaps we can at least find a common center again. An exploration of what led to the territorial claims staked on that identity, and the ramifications outlined above from the lack of diversity, that’s an exploration worth undertaking.

On Twitter, Leigh Alexander said recently that, on the relaunched Offworld, she’s avoiding the word “gamer” in favor of terms like audience and players. She says she feels these are healthier, and who can say if that’s true, but maybe there is something to the idea of a new label bridging a gap that, since September, has only seemed to widen. If we are all players, playing in our own ways, engaging on our own terms, perhaps we can find our way back to some common ground. There may not be a community to be had, one uniform whole under a moniker like “gamers,” but if we work to rearrange while understanding there is no homogeneity and we don’t want homogeneity — that it is time to move past the grizzled white cis-male hetero hero of every game, in every setting; that it is time to stop equating video games with trenchcoat-clad nerds; that is is time to expand our understanding of the interplay between what we play and who we are — then perhaps we can at least find a common center again. An exploration of what led to the territorial claims staked on that identity, and the ramifications outlined above from the lack of diversity, that’s an exploration worth undertaking.

But if we simply drop “gamer,” what does this do to the identities of the women who have grown up identifying as gamers? Women who saw themselves as a part of the community, and who fought for a place at that table? Doing away with the term gamer and attempting to start tabula rasa, in essence, attempts to whitewash the situation by negating the history and the experiences of the women who have struggled with and against the term all of this time. There is no way to erase the struggle of previous generations of gamers without erasing their identities. In the same way that we are morally obligated to face and confront other issues of inequity in our history, we have to confront the issues presented here and ultimately evolve. And we have to address the fact that GamerGate is not the disease, but a symptom of a larger global, systemic illness that relegates diverse voices to the fringe and limits their power and agency, even in something as seemingly benign as the community surrounding video games. This is the time for a bit of socialized medicine in the sense that it is the community that must come together to heal itself or find itself forever beyond repair.

2 thoughts on “Operation Bitter Pill: On GG’s Plans and Healing the Gaming Community”

You mention the impossibility of communication in the same breath that you call people “terrorists”. Even that aside – you mention this in an article about a goddamn BLOCKING device. You can’t have a discussion with people who got preemptively blocked.

If you truly want to have a discussion with proGG people, it’s not only possible, it’s SIMPLE. As long as you’re polite, it’s even very likely that the discussion will be civil and respectful.

Approach someone reasonable like @CultOfVivian, @lizzyf620, maybe TotalBiscuit… They don’t bite. If you have something reasonable to say, they’ll gladly listen. They probably won’t be swayed by empty rhetoric and buzzwords, that’s true, but I’m fairly certain they are kind, compassionate, and reasonable people.

I have. I do. I don’t use the blocker. I’ve frequently engaged on Twitter and in fact one night invited people to come and talk to me specifically about why they supported GamerGate. I wrote about that experience, here, on this very site, and I’ve attempted to unpack my reactions to the purported reasons behind GamerGate and how I have a hard time buying in to that aspect because I have a very different take on so-called games “journalism” and whether or not we can apply traditional standards at all. I also post from time to time on KiA, which is how I saw this in the first place.

And no, those conversations aren’t always civil. Sometimes they start out that way. Sometimes they don’t. I try to keep my temper. I am more than willing to have a conversation with anyone, anytime. What I’m not willing to do is allow someone to vent at me, insult me, or assume anything about how I feel or what I think, and why should I?

So let me turn this back on you:, rather frankly: if you truly want to have a discussion with me, it’s not only possible, but there’s a tag link on this very post. This is not the first time I’ve engaged with this topic. Do the work.

As for your specific comments on this, let’s not equate “I don’t feel like listening to you” with terrorist rhetoric. Sam and I did not make accusations; we looked at what was there, in print, and offered up our analysis, which is, you know, that thing we do. But blocking people, or refusing to listen, or yelling at clouds, or whatever, is not the same as employing, perhaps unknowingly, problematic rhetorical strategies. There’s enough here to talk about without resorting to either hyperbole or fallacy.