A quick stroll through the Playstation or Xbox stores reveals the distinct lack of a once-common feature: demos. A search of the Steam store returned 15 demos released since the beginning of June, most for free but some available only for purchase. Many of these demos, however, are for games that are inexpensive; many are tagged as indies. Several are visual novels, or otherwise interactive stories, games that don’t particularly need a demo, though the availability is nice. Don’t bother looking for demos of major releases or AAA games. These days, demos don’t sell games–streamers do. The footage is everywhere, linked to game portals along with both official and user-generated screenshots. This is good, many argue. This is the consumers doing it for themselves.

But can we call Pewdiepie a regular consumer? Stampycat? Jacksepticeye? TotalBiscuit? Many of the most popular streamers are supported in some way, either by sponsors or by their fans, and those who haven’t reached that tier are often gunning for it. This can result in performative, nonstandard gameplay, gameplay and commentary that ignores whole swaths of content, gameplay led and encouraged by chat, or just straight, great play — but even straightforward streams and videos don’t put the interface into the hands of the consumers like demos once did. Someone can tell you all day long how the buttons are mapped, but rarely will one player’s experience be exactly that of another.

That’s okay, because we also have reviews, right? What a glorious combination: hours of accessible gameplay footage from streamers, in a format that allows us to ask questions, along with all sorts of reviews from all sorts of outlets. Text reviews. Video reviews. Podcast reviews. Reviews that will or will not discuss representation issues; reviews that will or will not offer a score. Reviews that are sometimes embargoed beyond release date and time, or that may limit content or amount of footage, reviews that may or may not come from a free game or after a mega preview event. Reviews that may come out only after a venue favored by the studio has put out their early, exclusive, probably positive review. Reviews with scores that rarely dip below a 7, and are then often wildly controversial.

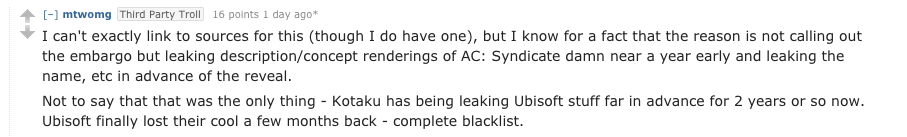

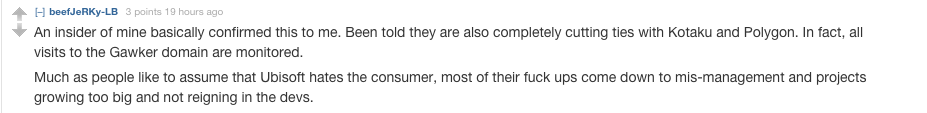

Kotaku’s Stephen Totilo addressed questionable embargo practices last fall (lambasting limiting embargoes and post-release embargoes especially, rather than embargoes as a whole), an interesting point in line with the recent news that Kotaku was not invited to Ubisoft’s E3 press conference. Why? No one’s really sure; the information surfaced on Jason Schreier’s Twitter in an offhand conversation, and may or may not be verified or changeable. Some are speculating about reviews and editorials attacking Ubisoft games over diversity issues. Whatever the reason, people are popping up on different gaming subreddits and offering inside info (that some are willing to confirm with mods) that Ubisoft is in fact blacklisting Kotaku over the Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate leak. There’s also talk of Ubisoft employees’ visits to Gawker being monitored, and a blacklist possibly extending to Polygon. But why? Over reviews? Are these things true? I can’t say. I think when we see multiple people offering to confirm, we can guess there’s at least some partial truth afoot.

Kotaku’s Stephen Totilo addressed questionable embargo practices last fall (lambasting limiting embargoes and post-release embargoes especially, rather than embargoes as a whole), an interesting point in line with the recent news that Kotaku was not invited to Ubisoft’s E3 press conference. Why? No one’s really sure; the information surfaced on Jason Schreier’s Twitter in an offhand conversation, and may or may not be verified or changeable. Some are speculating about reviews and editorials attacking Ubisoft games over diversity issues. Whatever the reason, people are popping up on different gaming subreddits and offering inside info (that some are willing to confirm with mods) that Ubisoft is in fact blacklisting Kotaku over the Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate leak. There’s also talk of Ubisoft employees’ visits to Gawker being monitored, and a blacklist possibly extending to Polygon. But why? Over reviews? Are these things true? I can’t say. I think when we see multiple people offering to confirm, we can guess there’s at least some partial truth afoot.

Here’s the thing: being blackballed from a press conference is not that big a deal, on the surface. Most of what happens at E3 is streamed anyway; we can all attend these conferences. But blacklisting a site from information and access is a much bigger deal. There are discussions with developers and teams and inside info that get passed around at events, and if major gaming sites are blocked for whatever reason, readers will turn to those outlets that do have that inside info, thus giving studios a great deal of control over how their content is presented. The fact of the matter is that studios can invite whatever sites and outlets they want, both in terms of rights–their events, their rules–and reality, meaning they could invite five random bloggers, and as long as those five random bloggers toss up info on their WordPress sites and talk about it on Twitter and maybe throw out an Instagram or post on some forums, someone will find it, and it will spread. That’s all it takes. Anyone could be a game journo, in theory, thanks to the Internet, just like anyone who’s entertaining enough can stream and build an empire. But just as with demos, when “regular folks” start replacing major outlets, there will be sacrifices. What do we lose next?

This is where GamerGate supporters might chime in and say, “nothing! That’s industry freedom, pure information from the consumer!” But that assumes Joe and Jane Random Consumers and Bloggers X and Y are unbiased, with no agendas of their own. That’s a mighty big assumption. I’ve never been big on using the word “journalism” to talk about the gaming press, except in a few cases, due to the nature and purpose of the press as an enthusiast entity, but the benefits of a team of professionals in any capacity is having people to double-check and follow-up, to have sets of standards and procedures, and rules, and editors. Maybe those rules are thin, maybe the editors are hands-off, and maybe every reader doesn’t agree with the team’s mission, but they’re there. Start bringing in niche sites, smaller sites, focused sites, and there’s possibility for change. Offer, too, a smaller site the chance to get bigger with exclusives….

But GG loves to hate Kotaku. At any given time on reddit’s Kotaku in Action sub, there are multiple threads dedicated to attempting to report the site to some authority for a disliked behavior, organized plans to try to hit ad revenue, or outcries against this or that writer for speaking out. It’s no surprise; hell, the sub is named after Kotaku, after all, so for many, this turn of events is seen as reason to celebrate. Oho, Kotaku’s going down! While it isn’t a universal cheer going up–there are dissenters frowning over this news of Ubisoft–the cheer is there. We’ve won; no one likes Kotaku and their social justice warrior bullshit anyway, so it doesn’t matter if companies are continuing some questionable practices. Does it even matter if perks are offered to streamers? Is that the same kind of ethical issue for GamerGate? Is blacklisting a website? Maybe not if it’s one GamerGate has boycotted.

After all, the discussions of ethical behavior are often bizarrely divided along lines that damn the “hated” sites and clear those GamerGate supports. For instance, users are constantly pointing to the fact that Kotaku runs stories about “sexism, racism, and harassment” that aren’t about games. That these stories are often related to games doesn’t matter; these are the factions that want politics kept out of games, after all. But Kotaku has always run actual non-game content, content about Japanese culture, films, television shows, and more, things that, while connected to geek culture as a whole, are far less connected to games than stories about aspects of games. Interesting, too, is that the 8chan board linked to GamerGate’s DeepFreeze site collecting so-called instances of corruption in the gaming press indicates that certain problematic pro-GG writers won’t be listed on the site because they’re not “game journalists.” The Ralph Retort, a site that for a time had a pro-GG tagline, is one of these examples. Of the ten posts visible on the first page of The Ralph Retort at the time of this writing, five were directly about games or gaming culture. All ten, however, are topics that have appeared on KiA, so while they may not be specific to gaming or gaming culture, those other five stories are relevant to a gamer-heavy audience’s interests.

After all, the discussions of ethical behavior are often bizarrely divided along lines that damn the “hated” sites and clear those GamerGate supports. For instance, users are constantly pointing to the fact that Kotaku runs stories about “sexism, racism, and harassment” that aren’t about games. That these stories are often related to games doesn’t matter; these are the factions that want politics kept out of games, after all. But Kotaku has always run actual non-game content, content about Japanese culture, films, television shows, and more, things that, while connected to geek culture as a whole, are far less connected to games than stories about aspects of games. Interesting, too, is that the 8chan board linked to GamerGate’s DeepFreeze site collecting so-called instances of corruption in the gaming press indicates that certain problematic pro-GG writers won’t be listed on the site because they’re not “game journalists.” The Ralph Retort, a site that for a time had a pro-GG tagline, is one of these examples. Of the ten posts visible on the first page of The Ralph Retort at the time of this writing, five were directly about games or gaming culture. All ten, however, are topics that have appeared on KiA, so while they may not be specific to gaming or gaming culture, those other five stories are relevant to a gamer-heavy audience’s interests.

One site posts gaming-related and non-game content, is still a gaming site, and tracked for unethical behavior by armchair watchdogs. Another site posts gaming-related and non-game content, is not labeled a gaming site, and the site-runner is allowed to run rampant, ignoring all pretense at objectivity and posting with a clear agenda in mind. Ethics?

No matter. What’s really important to highlight here is not the ins and outs of GamerGate and reactions to Kotaku, but rather the industry’s move away from, not toward, the consumer. Relying on news and reviews presented as entertainment, blacklisting major sites for whatever reason, ditching demos… these decisions do not benefit the people who purchase games, particular when those games are becoming more and more expensive all the time, especially when downloadable content is factored in. Maybe Steam wants to offer refunds for consumers (who will in turn use that feature as a sort of demo), but good luck trying to return that digital copy of any Xbox One or PS4 game because you simply didn’t like it or it wasn’t what you expected.

It’s hard to say the industry itself has ever been particularly consumer-friendly. Gaming is expensive, and a lot goes into creating content. Companies listen to fans off and on, but that lines their pockets, too; can’t recoup development expenses on a game that doesn’t sell. Companies are also invested in good reviews. Bonuses can be tied to Metacritic aggregate review scores, and GiantBomb’s origin story is a famous example of what happens when some writers don’t play the game the way people with more power want the game played. But things are changing, and fast; Kotaku’s Luke Plunkett wrote a parody piece about how the release and promotion of a game looks in the contemporary scene, and while it may not be designed as a defense against Kotaku leaking information, it can certainly be read that way. Information is leaked all over about games, all the time; videos get released early and by accident, screenshots surface, information is passed along social media, and sites have to make a decision: should we be the ones to publish information, or rumor, or leaks, possibly breaking embargo, possibly reporting something false? Someone’s going to do it, after all, but whom? How should it be presented, and where? Reporting the news is always a series of decisions, in any arena, and measurements of ethics can only take decisions so far.

It will be interesting to see what happens with E3, and with this rumor in particular, both how it is treated and discussed and what, if anything comes of it. It’s not the first time things like this have happened, and it won’t be the last, but we are also at a point in time that sees the number of major gaming sites shrinking, sites restructuring, and smaller sites cropping up with more specialized content. In a few years, we may be in an entirely different arena in terms of gaming news and culture reportage altogether… but how that looks remains to be seen.