Recently there has been a lot of discussion in the games community about criticism and objectivity. Questions have arisen such as: What is criticism, and what does it mean for the gaming sphere? What are the bounds of criticism, and what purpose does it serve? Is critique censorship? What is objectivity? Who gets to say what about games and what counts as a valid point of view?

Criticism in general is a systematic process by which we examine texts (anything is a text; everything is a text) using other texts in an effort to understand whatever there is to understand. This means that, as critics, we are making connections and drawing parallels between things that are sometimes connected and other things that are not. We are looking for symbols, cultural ties, and meaning. We are looking for some understanding, some answer or truth, even as we know that often no such neat answer exists.

Still, we interrogate. We examine. We analyze. We use a number of methods for this kind of exploration, from our personal experiences to various critical lenses. As a collective, we here at NYMG range from enthusiast critics with day jobs to tenured professors for whom this kind of work is the day job. We aren’t journalists here to report on news and developments; we aren’t reviewers examining if a game is any good for other people to buy. Sure, sometimes we report some news (editorialized); sure, sometimes we review games, but we do these things because we love games and geek culture. That doesn’t change who we are, and what we do. We are critics and scholars. And we are deeply embedded and invested in the community that we study.

Those of us branded “oversensitive,” “social justice warriors,” or both, are often told that we’re just looking for something that can be twisted into an offense, that we thrive on and perpetuate outrage culture. In a sense, this is true; we are looking for something, but it’s not an excuse to be angry (some of us don’t need one; we are like Bruce Banner in that regard, you know?). We are looking for those connections. We are looking at culture in a particular time and the artifacts produced from those cultures.

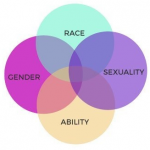

In the humanities, we talk about interpretation from different angles. We discuss authorial/creator intent; we discuss Barthes and the removal/separation of the author from the created work. We discuss whether or not an object has inherent meaning and then we strip away any meaning assigned (Saussure, Derrida, et al.); we deconstruct, dismantle, and destroy, only to build up and start again. Here at NYMG we attempt to pay homage to the notion of Intersectionality posited by Kimberlé Crenshaw as a means of looking at the ways in which distinct social/cultural/biological categories (like race, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, etc) overlap, affect, and are affected by systemic inequalities (like racism), with the belief that we all exist at the intersections of experience and knowledge, with our various literacies, privileges, indeed, our very lives and bodies defining what we see and how we respond to things. In the case of our work, those things, those texts, are pieces of media: games, comics, sometimes television shows and films, and just as two people can play the same game and say different and divergent things about the control scheme and graphics, so can two people play the same game and say entirely different things about the treatment and development of characters, the weight of plot… and whether or not certain imagery or plot points were unsettling to that person.

In the humanities, we talk about interpretation from different angles. We discuss authorial/creator intent; we discuss Barthes and the removal/separation of the author from the created work. We discuss whether or not an object has inherent meaning and then we strip away any meaning assigned (Saussure, Derrida, et al.); we deconstruct, dismantle, and destroy, only to build up and start again. Here at NYMG we attempt to pay homage to the notion of Intersectionality posited by Kimberlé Crenshaw as a means of looking at the ways in which distinct social/cultural/biological categories (like race, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, etc) overlap, affect, and are affected by systemic inequalities (like racism), with the belief that we all exist at the intersections of experience and knowledge, with our various literacies, privileges, indeed, our very lives and bodies defining what we see and how we respond to things. In the case of our work, those things, those texts, are pieces of media: games, comics, sometimes television shows and films, and just as two people can play the same game and say different and divergent things about the control scheme and graphics, so can two people play the same game and say entirely different things about the treatment and development of characters, the weight of plot… and whether or not certain imagery or plot points were unsettling to that person.

As scholars and critics, we catalogue and explore as many of those factors as we can, searching for linked imagery and historical connections through comparisons, or we count bodies and appearances as an examination of representation using quantitative methodology. We listen, recounting, and signal boosting stories of those who may not otherwise be heard using ethnographic methodology. We look at race as a system and as part of larger systems using critical race theory. We look at rape and rape culture through a lens of feminist theories of various waves. We make lists and we cross-list the things that appear on them because they intersect; we create a new layer of text atop the texts we explore.

The great thing about that new layer is that it exists on its own. It is there for those who want to engage with it, or build upon it further (just as a game exists for anyone to engage, or not, or mod, or not), and yet the layer of critique does not impact the original text, which still exists. This is how scholarly critique can diverge from more activist critique, which may call for some specific action. But this is not to say that all of our critique is inactive; often the action that we call for as scholars, teachers, and critics is to merely think. To consider.

Audience Engagement and Response

Just as we, as scholars, are initiating discussions, and entering those which already exist, we are opening the door for others to step into the conversation. This last week in particular, our criticism seemed to hit a nerve; while we received a breadth of responses here on the site, elsewhere response was almost singularly negative in regard to our examination of the Cuphead trailer, first, and then as we looked more deeply at Cuphead, Fleish & Cherry in Crazy Hotel, and classic animation. We are not alone in receiving these kinds of responses to controversial work. Critics of all stripes, particularly those who work in popular culture, are routinely flooded with negative responses when presenting an argument that may not reflect mass opinion. However, many of these negative responses are knee-jerk reactions, broad statements that serve as an attempt to shut down discussion rather than open it up. And those are the types of responses that we do not engage on the site. We are open to dissenting ideas and valid critique of our work, but we don’t engage with hate speech or disrespect of any kind. Our space. Our rules.

Putting aside all the abusive, hateful comments (the slurs, the suggestions that critics kill themselves or be killed, the remarks that this thing or that is stupid), there are a few things we hear most often when others engage (negatively) with the work we do, and we answer here just as broadly:

You’re just looking for a reason to get mad – No, we are choosing to analyze and respond to a text. This is circular anyhow; how is the creator of this kind of response not guilty of the same thing when they are angered by our response to a text, a response has no bearing on their personal well-being? (Translation: nah, you’re mad.)

You’re just seeing what you want to see – Or rather, we are seeing the world in the way our knowledge, literacy, lived experience, positions, and more have colored it. You may see things differently. Can we have a reasoned discussion about that divergence?

You just don’t like video games/comic books/etc. – Why on earth would anyone spend years playing games, studying games, writing about games, and learning, in some cases, how to make games, if they didn’t like games? If anything and everything can be a text, there’s no reason to choose to study a genre of text that you don’t love, particularly since you’ll be immersed in it forever.

But you’re all white/straight/rich/women – First, this kind of statement makes a lot of assumptions – some quite easily disproved by simply looking at our own breakdown of who we are, and some that cannot be determined at a glance. As a collective here at NYMG, we are a group with very different backgrounds and experiences, and when those backgrounds inform the work we do or are otherwise relevant, we talk about them openly.

Further, we also reject the idea that some subjects are off limits to certain people because of who or what they are. We do recognize that bodies and experiences inform the ways that we think about things, and that some may be uniquely positioned to best respond to particular events, but do not accept that, for example, only people of color can ever write about race. If we are to fully interrogate a thing (any thing) we have to bring a cacophony of voices to the table.

(And as a footnote, academics in the humanities are basically never rich; rich humanities scholars are like unicorns.)

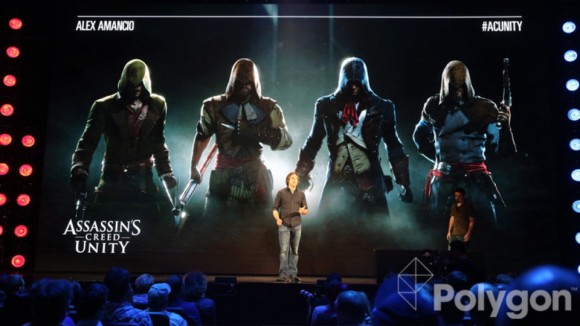

You just want to censor developers – Really? As critical game scholars we have no power over developers. Our power (like every other consumer’s) is limited to the money that we spend (or don’t) on the games that are released.

You just want to censor developers – Really? As critical game scholars we have no power over developers. Our power (like every other consumer’s) is limited to the money that we spend (or don’t) on the games that are released.

But this text isn’t racist/sexist/homophobic/transphobic/etc. – Unless a text outs itself as specifically posited against a subset of people, it’s difficult to take this complex measure, and more difficult to state unequivocally that a text does or does not evoke a particular response or include particular elements. This is a matter of interpretation; critical interpretation is based on documented examples and/or connections; experiential interpretation is based on the speaker, and so on.

And this last one is particularly important, because as stated earlier, there are often no clear, strict answers to questions raised by humanities scholars and critics. Criticism and analysis is an endless conversation, with speakers moving in and out, contributing their ideas and experiences, adding new layers of thought and discussion, but often not coming to the consensus that both sides may originally seek. And that is fine. Sometimes it’s not about the destination, but the journey.

5 thoughts on “Criticism on the Axes: On Intersectional Identity and Games Criticism”

Filthy GG supporter here but a good and thoughtful article.

My criticism of game criticism right now, and by extension this article, is that there are far more schools of thought available to scholarly criticism than what might be called intersectional criticism, or feminist criticism.

See literary criticism; the most commonly used and introduced school is ‘New Criticism,’ which doesn’t really care so much about a specific lens so much as it demands close observation of the subject matter in order to find contextual proof for the thesis. I’m frankly shocked that this kind of thinking isn’t the go-to method for game criticism as well, a kind of “close-playing” instead of literary theory’s close reading.

As a GamerGate supporter I’m not opposed to these mentioned critical schools, I’m just exhausted with how over saturated they are. Few, if any, other schools see mainstream attention or traction.

If games are to be regarded with scholarly criticism, let there be a diversity of thought that reflects more completely what that entails.

You raise a very interesting point about criticism and I agree, I love seeing lots of different criticism from many different angles. I think the lack you’re noticing comes from the fact that most games studies programs — and scholars in the field — are in rhetoric or communications, with some bleed over into American Studies. Lit hasn’t really picked up games as texts the way some lit-influenced scholars have taken on film and television, for example.

There is also plenty of argument for looking at games through feminist lenses in particular because of the collaborative angle. Whereas a single book may have been created by an author, with the influence of an editor or two, most games outside of indies are the products of vast teams, and so are by nature collaborative efforts. This is where our own Alex Layne’s Procedural Ethics comes in, of course, but it makes an easy marriage with feminist theory.

All that said, I love the idea of “close-playing” (great phrase) but considering the sheer depth of many games, and the factors that must be examined for any particular thesis, that seems to lend itself more to a book or series of publications more than a single one, but I hope that as more and more people get involved in games studies, particularly those from various (scholarly) backgrounds, we’ll see ever more expansion.

Now Sam will come in as the expert and tell me how everything I just said is wrong or something! She knows a lot more about the field as such than I do.

Thanks for the reply.

Yes, I absolutely agree that the depth and size of games can make them daunting for finding particular themes. In terms of New Criticism, though, the school of thought isn’t really focused on claiming that ‘X is THE theme of this work,’ but is more focused on ‘X is A theme in the work, and here’s the evidence I’ve amassed from the text to support it.’

This helps focus the scope of the examination a great deal, and makes the concept of close-play more accessible in larger games. For example, I’ve danced around with some notes and observations about how Fallout 3 and the Metro series both have strong themes about parenthood and the importance of parents as spiritual or moral guides. Superficially, it’s pretty obvious (more so in Fallout 3; the main quest line is literally chasing after your father), but there’s much stronger reinforcements of these themes for people who look for them.

It’s honestly why I like New Criticism and why I wish it was more prevalent; it’s a more open form of criticism. I like how it functions: it’s not about trying to see what a game looks like through the lens you’re applying to it, but more opening yourself to sensing what a game might be trying to express. Shedding lenses, biases, preconceived notions and simply allowing the game to present you with possible themes can be a challenging exercise, but a rewarding one.

Oh, I’m familiar; my prior work was in literature, though primarily in creative writing (which changes the way one studies theory, obviously) before I switched to rhetoric. All I’m saying is that it’s not as simple as quoting passages and identifying connections. Still, I think a lot of that can be done in other ways, and applying different critical lenses is not a matter of “let’s fix thing X into box Y,” but rather, “let’s explore thing X with the tools we found in box Y. You can — and I think, should — look at each text to see what’s there. What is the thing, what are the elements of the thing, how is the thing presented, etc., and then bring in other elements (creation of the thing, influences of the thing, connected things) depending on research angles.

A bigger (?) issue, as I see it, is not how criticism is performed, but that there simply isn’t a lot of criticism happening in public venues. Critical Distance’s roundup provides a weekly look at some of the work being doing, but with the clamor for video, I don’t wonder if many people are shy about producing longer critical texts (video or not). If they can’t be quickly summarized, easily quoted, and aren’t fodder for comment threads, will the traffic come? And that’s what most people are looking for. We have the luxury of being less concerned. We’re doing this work anyway; putting it on a website isn’t so hard. But not everyone is in that position.

To that last–I agree. There’s a precipice and a lot of people are all gathered up on the edge, waiting for someone else to step off first.

Related to being a GG supporter and to something I said in the first post, I like game criticism and WANT it to really diversify into schools of thought. I think criticisms like feminist criticism got to video games ‘first’ and staked a good claim, strongly aided by the fledgeling industry’s relative immaturity (in multiple senses of the word), and technical limitations that made for a lack of female characters, lazy trope, and shallow story.

Part of my GG-related criticism is that now the potential of criticism is far enough along that many sites have the power to diversify their examination of critiques, including hosting their own criticism or sharing thoughts on others’ work, but choose not to. Feminist criticism has become their ‘safe’ bet for web traffic or discussion because it still gets the easy clicks and heated discussion.

I think many of these sites are scared or uninterested in giving the rest of it a ‘trial run.’ I see it as a little hypocritical, as they boast game criticism as a strength but don’t do well to diversify it; talking about how good of a chef they are when they only repeat a couple of recipes out of the book. I’d love to see much more.